Titian and Palma Vecchio are credited with inventing these poetic “belle Veneziane”. Palma’s sumptuously-attired young woman is also known as Bella, “The Beauty”. She tenderly touches her hair while clutching her dower basket.

Titian’s

Vision

of Women

5 October 2021 – 30 January 2022

A major Autumn Exhibition 2021

400,000 visitors saw »Bruegel – Once in a Lifetime« in 2018.

⭑ ⭑ ⭑ ⭑ ⭑

340,000 visitors saw

»Caravaggio & Bernini« in 2019.

⭑ ⭑ ⭑ ⭑ ⭑

»Titian’s Vision of Women«,

this autumn’s highlight.

⭑ ⭑ ⭑ ⭑ ⭑

Beauty – Love – Poetry

Shortly after 1500, Titian in Venice began to produce paintings in which women were depicted in a new light. Inspired by contemporary love poetry and literature, Titian and his contemporaries – including Palma Vecchio, Lorenzo Lotto, Paris Bordone, Jacopo Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese – began to create poetic, sensual, idealizing (and ground-breaking) depictions of women that inspired European painting for centuries.

This exhibition examines the Venetian image of women in the context of sixteenth-century ideals and contemporary society.

In his paintings of women Titian celebrates them as the most splendid subject in life, in love and in art. High-calibre loans from international museums and collections join selected masterpieces from the Kunsthistorisches Museum to illustrate this fascinating, multi-facetted topic.

1

The ideal portrait: launching the “belle donne”

The feminine becomes the artist’s ideal

Once portrait painters discovered women as a subject for their art, the genre evolved from realistic likenesses to depictions of blond young women regarded as the ideal of feminine beauty in Venice.

Questions of identity are increasingly less relevant, although we can assume that each painting must have had a model/sitter. Here too the focus is less on verisimilitude than on erotic attraction, designed to cast a spell over the viewer. A beautiful body was regarded as the reflection of a beautiful mind.

Palma il Vecchio

Portrait of a Woman, called "La Bella"

1518/20

Madrid, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

© Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Titian

Violante

1510/14

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Her loose blond hair falling over her shoulders, Titian’s beauty – thanks to the violet in her décolleté she is known as Violante – faces the spectator/us, her gaze expressing curiosity without trying to “flirt” with the viewer. She is beautifully dressed and the fingers of her left hand form a “V”, something frequently found in contemporary ideal portraits of female sitters. This “V” has variously been identified as a reference to Venus, to virtue, or, in this case, to violets (viola in Italian). The small flower is a symbol of a young bride.

Some paintings are related and have evolved from

a single predecessor.

Titian

Portrait of a Lady ("La Bella")

1534/36

Florence, Uffizi Galleries

© Galleria Palatina e Appartamenti Reali di Palazzo Pitti, su concessione del Ministero della cultura

Titian

Young Woman in a Fur

1534/36

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Titian

Woman with a Plumed Hat

1534/36

St Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum

© The State Hermitage Museum, 2021, Foto: Dmitri Sirotkin

Newly restored, the ravishing paintings of "Bella" from Florence and the Hermitage’s "Young Woman with a Plumed Hat" are (re-)united with the panel now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

X-rays of the painting in Vienna reveal that the artist initially painted an exact version of the picture now in Florence before adding the now-visible alterations. This means the female sitter, originally lavishly-attired in a blue robe (La Bella, Florence), is increasingly sensualized: she still sports precious pearls and jewels and costly furs and hats but also reveals increasing amounts of skin.

2

“Realistic” Portraits

The leading Venetian masters produced surprisingly few identifiable portraits of individual female sitters. The small number of surviving early likenesses were executed on the mainland, where, as the heads of family clans, women generally played a more prominent role than Venetian women.

Titian

“La Schiavona”

1510/12

London, The National Gallery

© The National Gallery, London

This is generally explained with Venice’s tightly regulated and restricted form of government, where only men held power. Women were generally excluded from government and are therefore rarely present in paintings. Today, many of his female sitters are (still) anonymous, like the Schiavona now in London.

Portraits between reality and idealizing wishful thinking: art can make you young again

Titian produced portraits of famous women – the wives of the rulers of the many Italian principalities. Many of them he never actually met, basing his portraits on the likenesses by other artists.

Titian

Isabella d’Este, Marquise of Mantua (1474–1539)

1534/36

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Isabella d’Este was so bored with sitting for him that Titian had to make do with using earlier portraits of her as a model, eventually depicting the by now sixty-year-old marchioness as a dazzlingly beautiful twenty-year-old.

Family ties

The female sitters in some of his portraits have been identified as members of his own family: perhaps the most famous of these is the painting in Dresden that presumably depicts his daughter Lavinia.

Titian

Potrait of Lavinia

c.1565

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

© Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut

Titian and Workshop

Portrait of a Woman (traiditionally identified with Lavinia)

c.1565

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Jacopo Tintoretto

Portrait of a Young Woman

1553/55

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Other Venetian painters also produced portraits of female sitters. Tintoretto’s anonymous lady faces us with a surprisingly unceremonious directness. An early feminist who self-assuredly holds the gaze of any man who glances in her direction?

Anonymous

Portrait of a Young Woman

Brescia, c.1540

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

This beautiful but melancholic young woman remains an enigma. Is she indulging her dreams of love? Does her introverted attitude reflect the educated mind of a humanist?

3

Mirrors

The mirror as an instrument of complex visual

connections and a means of self-awareness

»In the mirror I try to recognize him who watches me through my eyes in the mirror«

Arthur Feldmann (1926-2012), Austrian-Jewish writer, emigrated to Israel in 1939 as Aharon Shadmoni, from 1956 in France as André Chademony

Titian

Young Woman at her Toilet

c.1515

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux

Beauty loves a mirror. The mirror, or the image it produces, was long a rival of painters who could only tame it by turning it into a subject of their paintings.

Giovanni Bellini

Young Woman with a Mirror

1515

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Mirrors not only allow us to control beauty, they also reflect it simultaneously from all sides. Thus, painting aims to surpass all the other arts including sculpture and even poetry.

Giovanni Bellini’s late work in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna may have inflamed Titian’s competitiveness. Like Bellini’s beauty, Titian’s “Young Woman at her Toilet” seems to be lost in thought while gazing at her own reflection; but she is not holding the mirror herself: she is being attended to by an admiring suitor standing in her shadow. Whose reflection is she gazing at in the mirror? Her own or his? Here, the artist is sounding out visual connections and pictorial limitations.

In another picture, the young woman has turned the mirror to face the viewer: it reminds us all of the transience of life.

Titian

Vanitas

c.1520

Munich, Alte Pinakothek

© bpk I Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen

4

Semi-nude deities on earth

The celebrated masters and their patrons literally elevated women to the heavens - their inamoratas were disguised as classical deities or the lovers of gods. A great favourite was Flora, the goddess of flowers. Bartolomeo Veneto and Titian produced very different but equally exciting masterpieces.

Titian

Flora

c.1517

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi

© Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture degli Uffizi, su concessione del Ministero della cultura

Bartolomeo Veneto

Flora

c.1520

Frankfurt, Städel Museum

Creative Commons, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Giorgione

Portrait of a Young Woman (‘Laura’)

1506

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Giorgione’s Laura is the epoch-making first in a long line of “belle donne veneziane”. By baring her breast, the painter depicts the moment a marriage is sealed. The bride showed her consent to the proposed union by opening her heart.

Bernardino Licinio

Portrait of a Woman revealing her Breast

1536

Bergamo, Private Collection

© Private Collection

Bernardino Licino’s painting too depicts this moment of agreeing to a promise of marriage. The remarkably individual portrait captures both the official and a very intimate moment of the union.

5

United forever

In love for five centuries

and still together

Love brings us together, lovers may end up becoming spouses. But love can also be accompanied by suffering – when it ends or your lover is taken away from you.

Bordone

The Lovers

1525/30

Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

© Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano

Bordone’s Lovers depicts the moment rings are exchanged in front of a witness, not a “ménage à trois”. Licinio captures the exciting moment the marriage covenant is sealed: overcome by emotions, the groom takes the bride’s hand, and she, to show her consent, opens her heart and uncovers her breast.

Bernardino Licinio

Young Woman with Her Groom

c.1520

Paris, Galerie Canesso

© Galerie Canesso, Paris

Giovanni Cariani

Young Woman with Old Man

1515/16

St Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum

Pavel Demidov © The State Hermitage Museum, 2021

The picture of an old man and a young woman is probably based on a now-lost composition by Titian. The youthful beauty was long identified as a muse inspiring an artist. However, unequal couples are a traditional and popular subject, a warning against deviating from the accepted moral value canon. Sex workers and sex fiends, adultery and greed are thematized tongue in cheek.

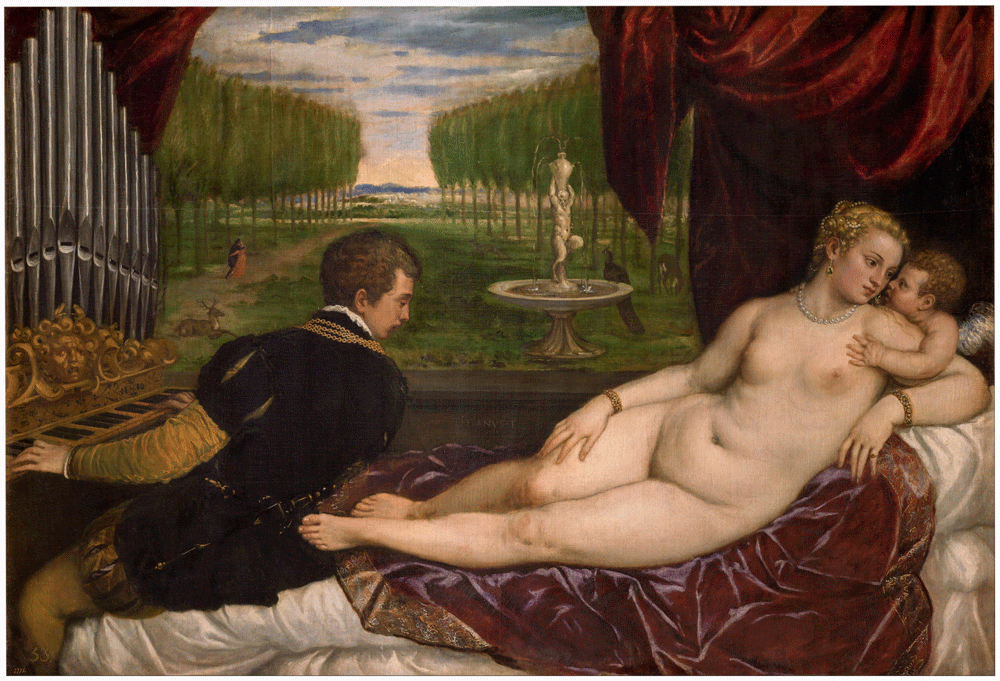

Music can spice up lovemaking. Music as a catalyst for love has long been a subject in painting, and it repeatedly appears in Titian’s compositions. A good example is “Venus with an Organist” . Harmonious sounds become a symbol of the hoped-for erotic union.

Titian

Venus with an Organist and Cupid

c.1555

Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

© Archivo Fotográfico. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Singers performing together are another way of depicting love. Here, Tullio Lombardo is helping a young couple to get in the mood.

Tullio Lombardo

Young Couple

1505/10

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

The young woman clutching the portrait of a man, which thematizes his absence, remains enigmatic. We cannot really tell if theirs is but a temporary separation or if he has died. But the composition bears eloquent witness to the ability of painting to replace an absent lover.

Bernardino Licinio

Portrait of a Woman Holding Her Husband’s Potrait

1525/28

Milan, Castello Sforzesco

© Comune di Milano, tutti i diritti riservati

6

The embodiment of virtue, courage and

devotion: heroines and holy women

Biblical and mythological women as models

Lorenzo Lotto

Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia

1530/33

London, The National Gallery

© The National Gallery, London

Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of a Woman is informed by “Lucretia” and confirms how the Roman heroine’s character and attitude were considered exemplary. Perhaps she and the sitter shared a first name, a popular choice in Venice at the time.

Valour, devotion and determination combined with chastity, virtue and humility are the characteristics of these sitters celebrated in countless paintings. Their stories may differ but they share one thing: their beauty. Because at the time a beautiful body also symbolised a beautiful mind.

Lucretia

The story of Lucretia proved a popular subject in painting. Lucretia committed suicide after she was raped by Lucius Tarquinius, the son of the last king of Rome, because she wanted to save both her own and her family’s honour, and for many centuries she was regarded as the personification of virtue.

Titian repeatedly returned to her story: in an early work he depicts her committing suicide, but a few decades later he focuses on the drama of the unfolding rape.

Because punishment of the rapist (Tarquin) resulted in the fall of Etruscan royal dynasty and the proclamation of the Roman Republic, Lucretia’s depiction also functioned as a political subject, epitomizing the moral foundations of the Venetian Republic.

Titian

Lucrecia and her Husband

c.1515

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Titian

Tarquin and Lucretia

1570-1576

Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste

© Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien

Paolo Veronese, too, depicted Lucretia taking her own life. But unlike Titian, who focused on the drama of Lucretia and her husband, he chose to portray her alone, in her final moments, shortly before she fatally pierces herself with her dagger.

Veronese

Lucretia

1580/83

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband

Judith

Women can also commit “male” acts and are celebrated for their valour. When a foreign army laid siege to her hometown, Judith did not hesitate but made plans to save it.

The beautiful widow visited the enemy general Holofernes in his tent, charmed him and made him drunk before killing him with his own sword and cutting off his head. Thus, Judith was able to preserve her people from being slaughtered or enslaved. Veronese’s Judith is pensive, she has just decapitated Holofernes and is still clutching his severed head. Her sumptuous clothes and precious jewellery set off her (for Holofernes) literally fatal beauty.

Veronese

Judith

c.1580

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Salome

Judith has always been depicted in ways very similar to Salome, Herodias’s beautiful daughter. John the Baptist had publicly castigated Queen Herodias for her depravity.

The mother then instrumentalized her daughter to kill him, and Salome performed a sensual dance for King Herod to force her stepfather to agree to John’s execution. Only after the saint has been decapitated does she realize what she has done: triumphantly but already somewhat apprehensively, she is displaying her trophy to the viewer.

Palma il Giovane

Salome

1599

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Susanna

Beautiful Susanna was taking a bath in her garden when two lecherous elders accosted and forced her to have sex with them. As judges they had the power over life and death.

After she refused their vile advances they accused her of adultery condemning her to death. Just in time, however, the Prophet Daniel managed to prove her innocence, and the two liars are executed.

Tintoretto

Susanna

c.1555/56

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Tintoretto depicts Susanna drying herself after her bath; her beautiful nude body is exposed less to the voyeuristic elders than to the viewer.

Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene, her long hair falling over her shoulders, her ecstatic gaze directed heavenwards, is among Titian’s most successful depictions of female saints. The master loved this composition and painted several versions of it.

Legend has it that he died clutching one of them. It is a highly sensual image of the saint, who lived as a penitent ascetic, praying for God’s forgiveness for her sins.

Titian and Workshop

Penitent Magdalene

c.1565

Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Creative Commons, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

The beauty of the female protagonists runs like a common thread through all these stories.

7

Sex object and goddess

Men writing about women

Sixteenth-century Venice was a centre of printing and publishing - a media revolution in the early modern era comparable to the disruption caused by digitalization today.

Content was reproduced faster and became available to a wider audience. A leading proponent in Venice was the publisher Aldus Manutius: he printed the works of classical authors for a highly educated target audience interested in ancient art and culture. He also published contemporary works in colloquial Italian, the “volgare”, reaching an even wider market.

Titian (attributed)

Portrait of a Man (Pietro Bembo?)

1515/20

Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie

© Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie –

Photographie Nicolas Waltefaugle

For women – of all classes – it became easier to participate in the poetic discourse and to establish themselves as poets.

Their texts, which criticize contemporary misogynistic attitudes and behaviour, clearly touched a nerve and document women’s new social status. A closely-spun network connected humanists and poets (male and female), poet-courtesans and Venetian painters. Titian was one of them.

Pietro Bembo is regarded as a leading Renaissance scholar and wordsmith. Bembo collaborated with Manutius, and with the latter’s support published the poems of Petrarch and Dante.

He helped establish vernacular Italian („volgare“) as the language of culture. Bembo’s Gli Asolani (“The People of Asolo”), a copy of which is on show in the exhibition, was one of the most widely read love treatises in the Renaissance.

Titian

Benedetto Varchi (1503–1565)

c.1540

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Benedetto Varchi, a humanist and art theoretician from Florence, commissioned his portrait from Titian during his sojourn in Venice. Nonchalantly leaning against a column, he clutches an open miniature book of Petrarch’s love poems – a small and cheap “petrarchino”; they were Aldo Manuzio’s most successful invention and a precursor of modern paperbacks. The central theme of many of the poems in Petrarch’s Song Book (Il Canzoniere) is his love for Laura, and they celebrate an ideal of beauty that lived on through the following centuries and inspired countless painters and sculptors.

Titian

Pietro Aretino (1492–1556)

c.1527

Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel

© Kunstmuseum Basel, Schenkung der Prof. J.J. Bachofen-Burckhardt-Stiftung, Foto: Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler

Pietro Aretino and Titian were close friends. The celebrated writer and satirist, who called himself “il divino” (“the divine”) and whose sharp tongue was feared by powerful people throughout Europe, vigorously promoted Titian and his paintings; the artist, in turn, portrayed him repeatedly. The portrait in Basle is perhaps the earliest document of their friendship. Aretino’s Ragionamenti, the “sensible dialogues” of two courtesans, are rightly famous. Written in a coarse, true-to-life vernacular, they are regarded as precursors of pornographic literature.

8

Women writers, poets and

poet-courtesans ensure that both they

and women in general have a voice

».. and, of course, Adam the first man was created in the fields near Damascus, while God created the woman in paradise on earth, a reflection of her greater excellence.«

Moderata Fonte (1555-1592)

Alessandro Bonvicino, gen. Moretto

Salome (Tullia d’Aragona, c.1510–1556)

c.1540

Brescia, Fondazione Brescia Musei

© Archivio fotografico Civici Musei di Brescia

Unlike of their male colleagues, there are but few painted portraits of the period’s numerous female authors, poets and poet-courtesans. Instead, we have to rely on prints.

In Venice, more and more of the women writing poetry came from bourgeois families. Their biographies are diverse. Some lived like nuns, remained unmarried until late in life, were widowed or so-called “honourable courtesans”; contrary to what we might presume today, the latter’s self-portrayal and presentation was comparable to that of elegant ladies, they hosted literary salons and socialized with artists, noblemen and members of the clergy. Male patrons helped them to publish their works. Self-assured and witty, they demand a new perspective on women.

»Women are called ›donne‹ because they are like a divine gift (dono celeste), without which there would be nothing either beautiful nor good.«

Moderata Fonte (1555-1592)

9

The splendid world of myths

Renaissance artists and their patrons regarded history painting as the apex of great art.

Titian

Venus and Adonis

1555/57

England, Private Collection

© Private Collection

Titian painted so many variations of some of these compositions, especially those depicting Venus and Adonis, that today we encounter them in museums all over the world. His works also informed the mythological paintings produced by his contemporaries: Tintoretto, Bordone and especially Veronese.

Titian was particularly famous for his depictions of classical myths.

The unrivalled dramaturge of colour imbued these bodies with a radiant brightness and embedded them in an atmospheric chiaroscuro from which white, red and blue stand out most strongly. Women’s varied roles, from powerful goddesses to nymphs who fall victim to Jupiter’s desires, are brought to life in varied, fascinating narratives.

The loves of the gods – painted poetry –

competing with poets

Titian created the Poesie for King Philipp II of Spain. They are painted poems inspired by classical antiquity.

In his accompanying letter, Titian explains the reasons behind his choice of subjects, which suggests he invented the compositions and selected their subject matters for purely artistic reasons. He also produced variations, which he then presented to other rulers. Titian was not only an artist commissioned by a patron, but also a humanist and writer.

Most of the subjects are taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses or the writings of other classical authors. In each of his compositions, Titian expertly chooses the moment in which the story is heading for its dramatic climax: Venus’s vain attempt to prevent Adonis from setting off with his hounds on what will be his final hunt. Jupiter penetrating the walls of the tower to visit, in the shape of a shower of gold, his lover Danae.

Titian

Danae

c.1545

Naples, Museo di Capodimonte

© bpk | Scala - courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali

Veronese

Rape of Europe

c.1578

Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

Foto Matteo De Fina 2019 © Archivio Fotografico -

Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

Paolo Veronese’s monumental “Rape of Europa” comes from the Doge’s Palace in Venice. Disguised as a magnificent white bull, Zeus abducts the beautiful princess and brings her to the continent that still bears her name.

In Venus’s realm

The goddess of love represents youth,

beauty and fecundity

The punishment of Cupid may be the result of the god’s naughtiness because he had, against his mother’s expressed wishes, fallen in love with Psyche. As punishment, his mother removed his instruments of power: Cupid is crying over the loss of his bow and arrows.

Tintoretto

Venus, Vulcan and Mars

c.1555

Munich, Alte Pinakothek

© bpk I Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen

Tintoretto’s ironic depiction of Venus and Mars’s divine adultery – with the latter hiding under the bed to escape the wrath of Venus’s cuckolded husband Vulcan – shows how much Venetian artists enjoyed devising and executing such subjects.

Titian

Venus Blindfolding Cupid

c.1565

Rome, Galleria Borghese

© Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali – su concessione della Galleria Borghese

Roman

Aphrodite Kallipygos

2nd cent. CE

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

© Su concessione del Ministero della Cultura - Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Foto: Giorgio Albano

Titian

Nymph and Shepherd

1570/75

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Lambert Sustris

Venus and Amor

1548/52

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle

Veronese

Mars and Venus

1570/89

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Open Access program, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

10

Allegories

Only Titian’s allegory for the ceiling of the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice has survived. Titian was actually a member of the jury charged with choosing the artist commissioned to produce these allegories.

His depiction of a woman clutching both a book and a scroll is generally identified as either an allegory of wisdom or of history.

Titian

La Sapienza (“Wisdom”)

c.1560

Venice, Biblioteca Marciana

© Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana

The ravages of time

Giorgione

La Vecchia (The Old Woman)

c.1506

Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia

© G.A.VE Archivio fotografico –“su concessione del Ministero

della Cultura - Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia”

This composition tells of time and the process of aging; note the scrap of paper inscribed “COL TEMPORE” (with the passage of time) in the old woman’s hand, her half-senile expression, her matt hair, her open mouth with but a few tooth stumps, and especially the tired, woeful rather than accusing manner in which she faces the viewer. This turns her into a moralizing allegory of transience.

Titian

Clarissa Strozzi (1540–1581)

1542

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

© bpk I Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,

Gemäldegalerie / Christoph Schmidt

Titian captures Clarissa tenderly feeding her cimabella, a ring-shaped breakfast pastry, to her pet dog, suddenly looking up as though hearing her name called. Despite her childish naturalness, the painting includes numerous clues to her future as a bride and wife, thus outlining her entire life: her dress looks like a wedding dress, the relief featuring squabbling cupids references future dangers of falling in love. But right now, she is still enjoying this phase of her life, her charming childishness and the love she feels for her lapdog, allowing Titian to turn this little girl into a lovable personification of human nature.

Titian

Triumph of Love

1543–1546

Oxford, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Programme

Private Guided Tours

Accompany our art educators through the special exhibition Titian's Vision of Women in a private guided tour in English.

Titian ‒ Online Guided Tour

Enjoy Titian in the Lockdown ‒ Online Guided Tour of the exhibition.

Join us on a tour and dream yourself into the special exhibition Titian's Vision of Women. Discover the Renaissance superstar and his contemporaries on an impressive tour. The link is available 48 hours after purchase.

Senior Citizen’s Special Titian with a Difference

Enjoy a unique visit to our exhibition: come and see our important autumn exhibition Titian’s Vision of Women: Beauty – Love – Poetry and discover Titian’s superb oeuvre. Conclude your visit with a snack in the museum’s sumptuous Cupola Hall.

Special Breakfast at Titian's

Enjoy a relaxed Saturday morning at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna visiting the special exhibition Titian’s Vision of Women incl. a guided tour and a small breakfast. Limited offer and dates! For our English speaking guests we offer the tour as an audio guide.

Venetian Evening Special

Do you want to enjoy an unforgettable evening? Book a Venetian Evening Special and visit the exhibition outside general opening hours with a guided tour, and end the evening in a relaxed atmosphere with antipasti and aperitivo. Book your ticket now – only a limited number of tickets available. For our English speaking guests we offer the tour as an audioguide.